by J. Mark Bertrand

It’s not enough to write what you know. You have to write like you know. All the research in the world won’t save you if you don’t master the art of writing with authority.

I should know. I write crime novels––police procedurals––and yet the closest I’ve come to wearing a badge is completing a private detective correspondence course as a teenager. And yet a real cop, reading one of my fight scenes, reported the action was authentic enough to make him reach for his back-up piece.

“Cool,” I thought. Then: “How did that happen?”

On my shelf is a novel written by a homicide detective. If the author bio is to be believed, the guy knows his stuff. Still, I couldn’t get through the story: it just rang so false. He was writing what he knew, but not writing like he knew it. You can tell the truth in such a way that nobody believes it, and that’s what this man did. He had authority, but he didn’t write with it.

So what’s the trick to writing with authority?

Tell the deeper truth.

Wear your knowledge lightly and focus on the visceral story realities, the emotional truth. Telling me if the rounds in the magazine are 115-grain or 124, hollow points or full metal jacket, isn’t nearly as important as making me feel what it’s like to have that muzzle shoved in my face. Get that wrong, and even if your facts are straight, I won’t buy it.

At the same time, don’t give yourself away. If you don’t know, don’t go there. My rule of thumb is, if I don’t know something without looking it up, I’m usually better off working around it. When you drop in undigested research morsels, the reader can feel it in his teeth.

Even if you do know, avoid the nitty gritty when you can. Castiglione preached the grace of sprezzatura, which amounts to never appearing to try too hard. Even when things don’t come easy, make them look easy. Learn that and you can write with authority when you’re not one.

Authors who spout facts come off like they’re trying to prove something, and authors trying to prove something rarely do.

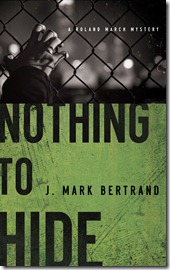

J. Mark Bertrand is the author of three crime novels featuring Houston homicide detective Roland March. The most recent, Nothing to Hide, was published in July 2012. He has an MFA in Creative Writing from the University of Houston and blogs about writing and the life of crime at CrimeGenre.com.

The head is missing, but what intrigues March is the victim’s skinned hand. The pointing finger must be a clue––but to what? According to the FBI, the dead man was an undercover asset tracking the flow of illegal arms to the Mexican cartels. To protect the operation, they want March to play along with the cover story. With a little digging, though, he discovers the Feds are lying. And they're not the only ones. In an upside-down world of paranoia and conspiracy, March finds himself dogged by injury and haunted by a tragic failure. Forced to take justice into his own hands, his twisting investigation leads him into the very heart of darkness, leaving March with nothing to lose––and nothing to hide.

4 comments:

I love your take on it. Writing what you know has to be the most ignored yet simultaneously touted piece of writing advice ever. How many of us has killed someone? But writing *like* you know sounds exactly right.

J. Mark, thank you for writing this. My main character for my series is a bounty hunter. I know enough to know what I'm writing about, but I'm not a bounty hunter and I only know how to use a rifle. My main character uses everything but a rifle. But it's not really about what weapon she has to use, what's most important is how she is engaged and how she reacts when she's in these dangerous positions. Readers do relate to that. Not one bookclub meeting I've attended has anyone asked me about the particulars in my story. They tell me how intense the scene was. How they could Angel's heart beating before she had to hurt someone. So when I read your article it made me feel really good. LOL. Because you're such a great writer, I have more confidence about what I'm doing. Thanks.

You know me, I have an issue with a lot of the writing maxims -- write what you know; show, don't tell, etc. -- or at least, with the way they've come to be misunderstood. I appreciate the chance to share!

Good post. I like this new maxim: "Writing what you know requires research. Writing like you know requires narrative verve." ;)

Post a Comment